Devaluation in RMB could counter tariffs, but would entail significant costs

21st October, 2019

In the UK, the seemingly never-ending Brexit saga dragged on, with parliament passing legislation that will force the government to ask for an extension if it can’t agree a deal with the EU. This sent sterling higher, which appreciated 1.09% against USD in September. As Brexit uncertainty continued to cloud the outlook for the UK economy, the Bank of England remained on hold. With wage growth at 4%, policymakers were conscious that if global and Brexit- related risks subside they may still need to raise rates, whereas if the downside risks highlighted by some of the business surveys materialized they would need to follow the Fed and lower rates. UK government bonds and equities delivered 6.7% and 1.0% respectively over the quarter. On the other hand, European equities delivered 2.5% over the quarter with growth pushing in one direction and monetary stimulus pushing in the other.

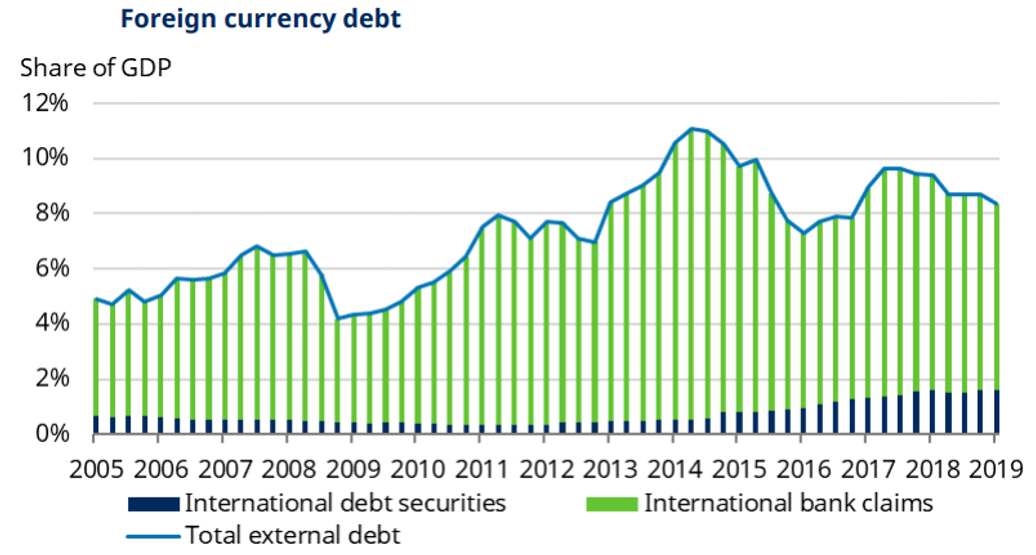

The renminbi took the strain as trade tensions escalate, and USD/CNH quoted at 7.14 at the end of September with offshore renminbi deprecating 3.8% over the quarter. Superficially, a devaluation seemed the obvious counter to 25% tariffs on all Chinese goods by the end of this year from the US. However, financial system could be weighed from it by the increased value of foreign currency debt and capital flight from the domestic banking system. While external exposures were limited as foreign currency liabilities were just a little over 8% of the GDP, capital out flow was a more serious concern although capital controls had been tightened considerably since 2015. Some currency weakness was a natural, and rational, market response to the trade war. The PBoC hoped that it is instead able to gradually guide the currency lower, until it reached a level at which even were the protective levees of the central bank to be removed it would not be washed away by the tides of the market.